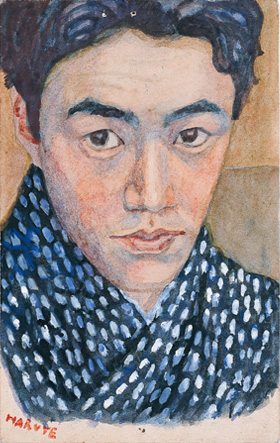

Koga Harue (1895-1933) is renowned for being one of Japan’s first Surrealist painters. As in his Innocent Moonlit Night, he assembled unrelated things to create unreal, fantastic worlds. Koga showed these works at the Nika Exhibition but remained largely unrecognized in his early twenties. At times, his work was even rejected by the Nika Exhibition. The words reproduced here are from “The Symbolic Nature of Watercolors,” which he contributed to an art magazine during one of these disappointing times.

Koga was deeply knowledgeable about poetry and admired Kitahara Hakushū, who was also from Fukuoka Prefecture. As a young man with literary aspirations, he crafted sketchbook in which he jotted down his poems modeled on Kitahara's tanka. Taking inspiration from Kitahara's poetry collection Kiri no Hana (Paulownia Blossoms, 1913), he likened oil paintings to novels and watercolors to poems. “Everyone will agree that a three thousand-page-long novel may be a literary masterpiece and a seventeen-syllable poem is weaker. In the same sense, it is not a problem if watercolors are weak. To be weak is their nature,” he said as he developed his aesthetic theory. Koga, who was then working primarily in watercolors, believed it important to capture momentary feelings brilliantly. He said that a painting without the power to grab the heart of the viewer at first glance was unfinished as a painting. But the medium in which this technique was best realized was watercolors, not oils.

He realized, however, that to win recognition from the art world and achieve success as an artist, he would have to produce oil paintings. Thus it was that Koga later turned wholeheartedly to oils. Then in 1922, he received a prize at the Nika Exhibiton and joined those who made up the center of the art world. In his writings from this period, we see him adopting a broader perspective and becoming an advocate for making full use of the respective characteristics of oil pigments and watercolors, instead of emphasizing watercolors alone. But while Koga continued to pursue a distinctive style in his oils, he continued to the end of his life to submit work to the Japan Watercolor Society exhibitions. He never ceased to regard watercolors as an important medium.

The early watercolors he produced in the first outpouring of his youthful sensibility remain relatively unknown. Let us bear mind the words with which we began in looking at them.

Curator:Eriko Ito

watercolor on paper

A watercolor is a poem, not a long novel. Please look at them that way. Watercolors are inherently symbolic poetry with a free, gentle, and also something-missing sentimental feeling about them. That is how they should be viewed.

“The Symbolic Nature of Watercolors,” Mizue, August 1920